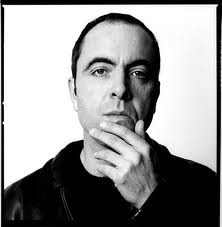

Actor James Nesbitt spent tens of thousands of pounds on what appeared to be a remarkably successful hair transplant. “They’ve changed my life. It’s horrible going bald. Anyone who says it isn’t, is lying,” said Nesbitt. Instead of the pitted sprouting potato look seen on many unfortunate recipients of hair transplants, Nesbitt’s hair looks convincing enough to help land him—he believed—major new roles that he would otherwise have been denied.

Actor James Nesbitt spent tens of thousands of pounds on what appeared to be a remarkably successful hair transplant. “They’ve changed my life. It’s horrible going bald. Anyone who says it isn’t, is lying,” said Nesbitt. Instead of the pitted sprouting potato look seen on many unfortunate recipients of hair transplants, Nesbitt’s hair looks convincing enough to help land him—he believed—major new roles that he would otherwise have been denied.The success of the transplant doubtless had something to do with the amount of money he could afford to spend on the job, but in the past, hard cash didn’t always solve the problem. “All that money and he’s still got hair like a dinner lady,” spat Boy George of Elton John, who has appeared to unsuccessfully confront his receding hairline with various ineffectual treatments over the years.

But this time, the transplants were actually pretty convincing. What was going on? There were rumors that a new hair transplant technique—FUE, or Follicular Unit Extraction, which transplants follicles from the back of the head one by one instead of in a long strip—used robot technology to enable thousands of follicles to be replanted at once, thus producing a more sophisticated and convincing result. Perhaps a new crop of hair could be bought, right now, without having to wait for genetic science to take the necessary leap forward.

Murray Healy, journalist and author of the book Gay Skins: Class, Masculinity and Queer Appropriation, points out that losing hair naturally is “seeming to fail, which is a bad thing. Thinning hair is, in a sense, the equivalent of a ‘failed crop’.” By which he means a failed agricultural rather than tonsorial crop.

He suggests unhappiness at not having hair is to do with a sense of shame, rather than any objective reality; and that if one is bold and does nothing to conceal the loss, and in fact emphasizes it by shaving, it can signify the opposite of failure—confidence in one’s own masculinity. This is a fairly recent phenomenon, which can be traced back to the hyper-masculinity advertised by the original skinheads in the 60s and 70s, a hairstyle which was then appropriated and lionized by the gay community in the 80s and 90s and turned into the opposite signal.

No comments:

Post a Comment